|

Conversation with Jane Goodall

by Marianne Schnall

2010 marks 50 years since Dr. Jane Goodall first set foot on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, in what is now Tanzania's Gombe National Park. The chimpanzee behavioral research Dr. Goodall pioneered there has produced a wealth of scientific discovery, and her work has evolved into a global mission to "empower people to make a difference for all living things." The 76-year-old world-renowned primatologist and UN Messenger of Peace also has an inspring new book out, Hope for Animals and Their World: How Endangered Species Are Being Rescued from the Brink and her own organizations, the Jane Goodall Institute and Roots & Shoots, which aims to empower and educate youth.

I had the opportunity to talk to the legendary naturalist , who was in a reflective mood, sharing openly her wisdom and insights. Whether talking about the significance of her life's work, the state of human evolution, her attitude towards aging or her definition of God, she was passionate and profound. Her hope for the future? "That basically we come to our senses! That we really truly do start regaining wisdom... and join our hearts to our heads."

INTERVIEW WITH MARIANNE SCHNALL (2/11/10)

Marianne Schnall: This year marks the 50th anniversary of your arrival in Gombe, Tanzania, and all that has resulted from your groundbreaking research on chimpanzees, which is now one of the longest running studies of a wild animal species. How do you feel about this anniversary?

Jane Goodall: Well, it's very extraordinary to me to think that half a century has passed, that we're still studying the same community, that we're still learning new things, that students who've have been through Gombe have now gotten university positions all over the world, and that it's impacted probably thousands of people by now, not just the foreign visitors coming in, but Tanzanians as well.

MS: How do you think your vision and mission has expanded since then?

JG: Well, enormously. It was just concerned with learning about the behavior of one group of chimps, then realizing that chimps across Africa were becoming extinct, then travelling around Africa and talking about conservation. And then realizing how many problems in Africa are due and left over from colonialism and the continued exploitation of Africa's resources. So travelling in Europe and Asia and North America and realizing how many young people have lost hope, and so starting the program for young people, Roots & Shoots, which now in 120 countries. And that involves young people from preschool right through university. So I don't know how many active groups there are, but it's pretty amazing.

MS: If you had to look back and pick important milestones over the past 50 years, which milestones or defining moments come to mind? For example, the discovery that chimpanzees use tools.

JG: Well, using and making tools was the first - well, actually even before that the first day that a group of chimps let me come close was pretty amazing. Then the tool-using and tool-making, definitely. And hunting and eating meat happened very soon after. And then the day that David Greybeard took the nut from my hand and then didn't want the nut, then very gently squeezed my fingers like chimp reassurance, which was a clear communication between me and him - it was a very extraordinary moment. And then the conference at which I realized that chimps were becoming extinct in 1986 in Chicago and realizing the extent of suffering of captive chimps and that took me on the road - I call it my Damascus moment. I went in as a scientist and came out as an advocate.

MS: Which brings me to your important new book, Hope for Animals and Their World. If you had to distill it, what message are you most hoping to convey?

JG: That people should never give up - that there is always hope. That, OK, the natural world is in a real crisis situation, but there are all around the planet extraordinary people who are absolutely determined that certain animal species or plants or ecosystems shall be helped to restore themselves. And the success stories which are in that book. And it's very inspiring to young biologists and botanists who want to set out on this kind of career and are always told it's useless because it's too late. So this book is very important in that respect. If we all give up hope and do nothing, well then indeed there is no hope. It will be helped by all of us, every one of us taking action of some sort.

MS: Sometimes people honestly just fail to see how these issues are connected to their lives. Why is this all so important, biodiversity, conservation, saving endangered species - how is it connected to their lives?

JG: Well, it's connected in that we learn more and more how everything in this life is interconnected. And things which go on in let's say the Congo Basin- it may seem incredibly unimportant in the Midwestern United States, but then when you realize that the loss of the tropical forests in the Congo Basin is having an enormous effect on climate change, and climate change in turn is effecting weather patterns all over the world, then you start to realize that life is interconnected. Then, on the other hand, maybe there may be some small ecosystem and there may be an endangered species, it may be an insect and so what if it disappears, you know? But maybe that insect is the main prey of a certain kind of bird, and if the insect goes, the bird goes, and maybe that bird was important for dispersing seeds of various plants and so those plants will start becoming extinct - and one thing leads to another. And none of the biologists know where it's going to stop. So the answer to it really is that we know we are all interconnected and we don't yet know the effects of removing a strand from the web of life.

MS: I am living in the country but I grew up in New York City, and I only realize now living in the country how disconnected I was from nature. Do you think that's part of the problem, that we've lost that sense of connection. What do we miss out on, and what can we do about that?

JG: Well, it's been shown several times that contact with nature is actually important for psychological development and so children who are in a concrete jungle with, as you say, little opportunity to learn about the natural world, or equally children everywhere who are glued to their computer screens and computer games - I mean, you know this is becoming really frightening. What can we do about it? That's why Roots & Shoots to me is the most important program that we have. Because one of its aspects is very definitely that if you can't get the child into nature, then bring nature to the child.

MS: Tell us more about Roots & Shoots and its work to educate and empower youth. What does it aim to do?

JG: What it aims to do, first of all - its main message is that that everyone of us makes an impact on the world every day. And so it's helping individuals to understand that though they may feel their small actions don't make a difference - which if it was just them, they would be right probably. But it's not just them and cumulatively our small decisions, choices, actions, make a very big difference. So that's one thing. The other is that it's youth driven, so it's young people sitting around either on their own or at their high school or university, or sitting with the teacher if they're children in Kindergarten or first grade, or with parents, or with older children - it's doesn't matter - thinking about the problems around them, talking about them, and then between them choosing three projects that they feel would make things better: one for people, one for animals, and one for the environment. So, in almost any group of kids, you get those passionate about animals, you get some who want to really, really do community service for people and you have some who want to recycle or clean streams or something like that. So every child can become involved in a project which they helped to choose and about which they feel passionate.

And it's working - I mean, it's changing lives. I can't begin to tell you how many lives it's changing. I think this is why it's growing so fast.

MS: I think it should be bundled into the curriculum at every school.

JG: It should. And that's what we're trying to - you know, Roots & Shoots, people don't always understand, but it can be part of a curriculum, or aspects of it, to be part of general learning. And from those children, who are exposed to this philosophy, you can get very passionate ones who then want to become leaders. You know, we have youth leadership programs - we're seeing young people emerge who speak out and speak and I listen to them - and we brought a hundred of them together from 28 countries. And it was amazing to hear them discussing all these different world problems. They were 18 through 24. And it was so inspiring! And so everywhere I go, 300 days a year, all over the world, there are young people wanting to tell Dr. Jane what they've done to make the world better. Shining eyes, showing me projects, telling me about their dreams - that is my greatest reason for hope.

MS: You have vibrant web sites both for the Jane Goodall Institute and for Roots & Shoots, and I was thinking about how language is what distinguished humanity from all other animals. Do you see the Internet as an extension of the positive use of language to raise awareness and get people involved?

JG: Yes, absolutely. I mean of course, sadly it can be used for bad purposes, but as long as it's used for good purposes, it's fantastic! I mean, we're counting on it to swell our membership because my big battle is not just for hearts and minds, which is the most important, but also for the dollars to help to keep our programs going.

MS: And what I love about the Internet is that it is global. The more that we see ourselves as being part of one human family here on one home, planet Earth ... I think that's so important.

JG: It's very important. I mean, start off with your own community, start off with stuff you can do, so that you actually see. Okay, you want to protect a piece of rainforest far away, you raise money and then you feel, "Oh, nice, I've protected that bit of rainforest so maybe a jaguar will be saved." And you've raised money. But if you're protecting a piece of land near your school from developing, you've learned the difficult part of conservation because maybe the developer is your best friend's father - and you start to realize that saving things isn't always easy, and choices must be made and compromises have to be reached. That's when you learn the reality. And then if young children begin to learn that - not too young, but like 12 or 13, then when they grow up and come into the big, hard world, they already know that you don't give up if it doesn't work the first time - you find another way. That's what's really, really important about it.

MS: You were talking about reaching people's minds and hearts. Do you feel there is a growing disconnect between human beings today and their hearts? In terms of how we treat animals, the environment and each other, and how we don't think about future generations, just of our own instant gratification?

JG: Yes, we don't think about our future. We do think of it, it's just - I say we've lost wisdom. We're thinking not as the indigenous people did about how our actions affect the future of their people, but we're thinking about, as you say, instant gratification for me, or the next shareholder's meeting, or the next political campaign - that sort of thing. And so just as you say, the disconnect between the head and the heart - this very, very clever brain, if it's disconnected from the human heart to speak of love and compassion, then we get this individual with complete lack of caring, lack of foresight, just cunning.

MS: You talked about how kids these day can spend all day in front of the computer - you used the word "mindless activities" in your introduction, and it seems like part of the problem is that we're so over-stimulated and almost on autopilot, that often we don't have the time or the mindfulness to even realize what we are doing.

JG: We don't! We don't. I think when people say to me, "Jane, I really want to help, what can I do?" If people could just spend time a bit of time each day thinking about the consequences of their choices. Like what do you eat? Well, that may seem simple, I ate this or that today - but where did it come from, how many miles did it travel, did it harm did the environment, how much pesticide was used, was it child slave labor? If it was intensive farming, how did that affect the animals? How did it affect the environment, and how did it affect your health? The same with what you wear, how you travel, how you connect with people - if people would just start thinking about the consequences of all these small actions. But as you say, it becomes mindless, people don't think.

MS: I have been thinking that there seems to be a growing awareness about the interconnection of all the issues that are impacting our world, whether it's poverty, war, the environment - and how we can't address one area without looking at how it's all connected.

JG: Well, I think there is a growing awareness among the people who think - that means an awful lot of people aren't aware. But you know the other thing is, they did a survey in the UK the other day about climate change. And they found there was a huge awareness among all kinds of people about climate change, but almost never has that led to change in behavior. There's another disconnect. Again, it's because people don't believe that their actions really and truly are going to make a difference. But kids get it. They know. And they get all excited about the difference they're making. And I always say to them, look at the difference you've made here in your one little group, and your little area, your one little community. Now imagine that's happening in 120 countries, with I think about 1,500 groups, with a group averaging about 30. That's a lot of young people.

MS: That is very hopeful.

JG: It's very hopeful. And suddenly - you know the little saying, "Think globally, act locally" - no, act locally first, see that you make a difference - then you dare to think globally. There are so many little trite sayings that people trot out and they don't actually think about them and how it might actually work. There's another one which irritates me every time I hear it - it's "We haven't inherited this world from our parents, we've borrowed it from our children." When you borrow, you pay back, right? Or you should do that. We have been stealing and stealing and stealing from our children. And now it's about time we started to get together and involve our hearts and pay back.

MS: What is the relationship between political activism and working towards change with these issues? In addition to personal activism.

JG: Well, I think it's important. We teach our Roots & Shoots children at least a little bit about how to write letters and how to advocate and how to peacefully protest and that sort of thing. I think people should get involved whenever they can - as long as they're not violent. As long as they listen to the opponent, they listen to the other side, and they don't just shout and yell. And you hear, sadly, some animal rights groups who don't listen at all to the people they are going to shout down. And they don't get anywhere and they give us an awfully bad name.

I mean, I do lots of lobbying on the hill but it's not really lobbying, it's just going and talking.

MS: How do we balance the needs of human beings and animals? Human beings tend to think only about our own needs and assume that everything on this planet is just here to serve us.

JG: They do. Well, it's very hard, I mean, first of all that's the importance about educating people who animals really are and that they are not just automatons and they deserve an inning as much as we do. And secondly there are too many people on the planet and everyone's afraid to talk about family planning, but that's interfering with people's right to choice to have a huge family. Well, I don't think anybody has the right to a huge family. There's already more people on the planet than our natural resources can even support, and if everybody were to have a high standard of living, we need three or four or five new planets to provide the resources. And this cannot be, so something has to change.

And I get also upset when so many people say there all sorts of problems in Africa and India where they have these big families. They don't realize that 10 children in rural Tanzania will use less natural resources in a year than one middle class American child. People don't think like that, you see.

MS: Do you see hypocrisy in how we sometimes treat domesticated animals such as our pets over wild animals? An example would be someone who pampers their pet hamster in one room, yet kills rodents in another part of their house using traps and poison.

JG: Yes, that's very true. And you get the white coated scientist who has a dog at home who's part of the family who understands ever word I say - but then he goes and puts on his white coat and does unspeakable things to dogs in the name of science. There's a real schizophrenia. Yes, we are very peculiar [laughs].

MS: What do you think is the relevance of Darwin's theories today?

JG: Well, relevant - I think that his theory, I don't know, as far as I'm concerned his theory is always good - not in every detail, but generally. We've evolved and I've held the various fossils in my hand. It's fascinating to see the evolution.

MS: Do you see the human race as still evolving?

JG: Well, I think we've sort of embarked on - we started off with physical evolution and got our form. And then we moved into cultural behavior means you can parse behavior much more quickly. And the chimps have just begun that, but they haven't gone very far. And then we somehow developed language, which meant cultural evolution could race so we could change our behavior really quickly instead of over hundreds and hundreds of years. And then comes moral evolution, which we're not frightfully far along I think with people. And maybe we end up with a spiritual evolution, which is this connectedness with the rest of the life forms on the planet.

MS: Wouldn't that be wonderful.

JG: That's the human destiny that people would write about, to move in that direction.

MS: I run a women's web site called Feminist.com. And a lot of people think of you as a woman trailblazer in your field and I know you have also done a lot of work regarding women in developing countries. What do you think about the status of women and girls in the world today?

JG: Generally, I suppose if you just added up the number of abused women it would probably far outweigh the privileged women. I hate to say that. But certainly across the developing world, many countries and many parts of many countries have not come very far in treating women with dignity. In a large part of the world, women are second class citizens. And then in our own so called civilized countries, the amount of domestic violence that is uncovered all the time is shocking. So I think women are still getting a hard time, I'm afraid.

MS: How do you think your work may have changed perceptions of the role of women in the field of science?

JG: Judging from the number of young women who've wanted to follow in my footsteps [laughs] I should think it has changed it a lot! I mean, I know that. Women come up and say ... like in China, a young woman came up and burst into tears because she'd been studying pandas and thought that school girls didn't do that sort of thing and then read my book, and so there she was. And so this has happened to me all over the world, certainly all around America, young women have said, "You really helped me break out of the mold, you really helped me realize it could be done." And kids write and say, "You taught me that because you did it, I can do it." Those are the letters I love the most.

MS: Many women fear getting older and you seem more active and vibrant than ever. What are your feelings about aging?

JG: Well, it's an unfortunate thing that happens. I mean, yes, you can have millions of face lifts and all these different things that women have done to their bodies - whatever they're called, bum tucks and boob enhancements [laughs] - but personally, well: A) I haven't the money for that, and B) I haven't got the time for it and C) I mean, there are more important things to me than how you look. I think the most important thing is to keep active, and to hope that your mind stays active. I mean some people can't help minds going, but that's a disease. But if you're lucky and your mind is working ... And I have to say that I attribute vast amounts of my energy to the fact that I stopped eating meat. I really, really believe that it helped me.

MS: In what way?

JG: Because the moment I stopped eating meat I felt lighter. I did this book Harvest for Hope and I learned so much about food. And one thing I learned is that we have the guts not of a carnivore, but of an herbivore. Herbivore guts are very long because they have to get the last bit of nutrition out of leaves and things. The carnivore guts are very short, because they want to get rid of the meat quickly before it starts putrefying and doing bad things inside them. And so we have this meat going round and round inside us. And I don't think that can be terribly good. And I think that meat has created lots of problems. In addition, the animals to be kept alive are fed all these hormones and antibiotics and we are imbibing them as well. So anyway, all I know is that when I stopped eating meat, I just felt lighter and had more energy. My body wasn't wasting time trying to cope with the toxins that the animals were trying to get rid of when you eat them.

MS: Well, that's good to hear because I have been considering going vegan.

JG: Well, I can't go vegan because travelling like I do, I really, really don't think I could. You know, it's really difficult. And I stay with people - we had a vegan staying us one time, and it's very difficult. Three hundred days on the road - you go to North Korea - it's jolly hard to be vegetarian much less a vegan [laughs]. But I do my best. And if people would think about intensive farming - if they would think of the damage to the environment of growing all this corn or raising all these cattle. If they would think about the torture of the animals on the intensive farms. And then if they would realize about the antibiotics getting out into the environment, the bacteria building up resistance and the superbugs that we are breeding, more people would become vegetarians.

But if you can let people know about Harvest for Hope , because it's not just talking about all these things and genetically modified food. It's written in a way that, to my amazement, people would come up to me and say, "I really enjoyed that book, it's such fun." So you can enjoy bits of it and that's how you get a message over, isn't it? So I would love it if you can tell people about that book.

MS: What do you think about zoos? I know you talk a lot about good zoos and how zoos can help with endangered species.

JG: Well, not only that, but the way I look at the zoos, there are some - obviously the old fashioned zoo is an abhorrent thing. You know, the small cages and single or paired animals and nothing to do - those are just the most dismal, awful, awful prisons. But if you get a good zoo, and there are a lot of zoos that are getting better and better and they have to raise money, of course, but they are. And again, being a realist, the ideal way for an aging chimp to live is out in Africa in a protected area like Gombe. That's the ideal. But sadly in so much of Africa, there's no protection, there are hunters, there are loggers, and the chimps are living in fear, their mothers are shot, babies are taken, and they are driven out of their habitat and they bump into the neighboring communities who just want them there to have a sort of war. And then you look at the other end of the spectrum, the medical research, the five-foot by five-foot cage and the bad zoo and the awful life of an entertainment chimp.

And then when you come to a really good zoo, where the chimps are in a group where the keepers understand them and love them, where their environments are enriched. And you think, well, if I'm a chimp, and you give them that range of habitats to choose to live - there would be two where they chose to live. One would be the Gombe type, and the other would be the good zoo type. We have this idealized view of freedom. And even for people it doesn't always work. That they're going to get freedom and suddenly their lives will be wonderful. And same with the chimps - you know, life in the wild, they may be free but they're not free from fear, pain.

MS: What is the most important point you would like to raise awareness about right now? Where is the most important area for change?

JG: You know, it's so difficult. People ask that and you think well, okay - you come back to - I think a really, really important thing is thinking about the size of our families - that for some people that is very, very important. Because all of the other problems really come down to the basic fact that there are so many human beings on the planet, it means that there is competition between people and the environment. And so the numbers of people on the planet is something that we really should be thinking about, but also, people should plan their cities better. You wouldn't get urban sprawl - you could have areas left for wild animals and you could have the human population living in such a way that you've got these big corridors and spaces where the animals could move from A to B. It is happening. You can put roads just as well over above a piece of wild habitat as by chopping down the trees and building it across. Yeah, it will cost a bit more. And what do we want for the future? If you think how we waste money - if we could just stop building up armies and things like that, we would have all the money we need for wildlife and poverty.

MS: You are such a tireless advocate. What do you think is the source of all your phenomenal energy and passion? What drives you?

JG: I don't know. I really don't know. I people are always asking me that. Is it that I have grandchildren and I'm so upset about what we've done to their future? Is it that I love the wilderness and I'm so upset to see it disappearing? Is it because I've lived long enough to understand the horrors of things like nuclear war and chemical spills? I don't know. But there is something almost every day that makes me quite passionate, so I'm trying to create change. There is not much you can do singly, but if we can involve young people, especially at that age I mentioned, 18 through 24, going out in the world as the next politicians, the next lawyers, the next doctors, the next teachers, the next parents - then perhaps we get a critical mass of youth that has a different kind of values.

MS: Based on your research, what does it mean to be human? What distinguishes us?

JG: Well, I suppose it's because we've developed this language which has enabled us to talk about things that aren't present. We are in a position to understand our relation to the rest of the planet. We can ask questions like, why am I here? And do I matter? And I think that's what's makes us different, that we can question the reason for existence. We can question why we're on the planet, our role.

MS: Speaking of which, in your opinion, why are we here? What do you think is the meaning of our life and existence?

JG: Well, I think we're here - you know, we each have this one life gifted to us. And I feel - and I'm not going to say this in general, but I feel that my life is a gift that I want to try to use as wisely as I can, and I want to make use of each of these amazing days that come my way to try and make a bit of difference. To think things through, perhaps get new ideas, to talk to people, to write, to do my bit. And you know, you get certain gifts, and I had a gift of speaking, lecturing, which makes people listen. It's a gift - it's an amazing gift. And I have the gift for writing. So I must use those gifts, and I try to.

MS: We were talking a little earlier about this spiritual evolution that humanity is hopefully moving towards. How would you describe your own spiritual beliefs? What is your definition of God?

JG: Well, God - I think it is different for everybody wherever you were brought up in different parts of the world, unless you are born to an atheist family, which Richard Dawkins would like us all to be since he's so passionate about it [laughs]. But in every religion there is a being, a deity, usually with different names, God, Allah and Taos and these types of names. My mother always used to say, well, if you had been born a little girl growing up in Egypt, you would go to church or go to worship Allah, but surely if those people are worshipping a God, it must be the same God - that's what she always said. The same God with different names.

And exactly what is God - I wouldn't even like to begin to define God - I have absolutely no idea. But what I feel, and what touches me, is a great spiritual power, which I don't even want to name. If I had to, I would say God, because I don't know any other. And you feel it, I felt it very especially out in the forest, out in nature. Being part of the whole, the amazing, extraordinary universe. To be looking up at the stars, that tiny speck is capable with its mind of trying to comprehend the whole. And it's extraordinary that we should be able to do that.

MS: People think of you as the voice of the animal world. What does the animal world, what do chimpanzees, what would they say if they could speak? What is the voice of the natural world?

JG: The voice of the natural world would be, "Could you please give us space and leave us alone to get along with our own lives and our own ways, because we actually know much better how to do it then when you start interfering. " You know, give nature space - it is resilient. Unfortunately we've messed it up so much we have to go in and manage very often. We have to, otherwise they would all disappear. Which I don't think they want to be managed - they might want to be helped from time to time.

MS: Many people think of you as a living legend. What do you think is your legacy and what would you like to be remembered most for?

JG: Well, partly for helping people understand the true nature of animals and to better understand their relationship to the rest of the natural world. And I think my job has become nowadays bringing hope to people. Because I think that's my job.

MS: What's your wish for the children of the future, or just in general for the future?

JG: Well, without the children there's no future. That basically we come to our senses! That we really, truly do start regaining wisdom. If we just regain wisdom, and join our hearts to our heads, then I think in the future we would not be making the decisions that some of these big multinationals are making. We wouldn't decide to throw pesticides over huge areas of the land knowing it's actually going to harm not only the pests, but the biodiversity and eventually us. We wouldn't be building nuclear plants not knowing what to do with the nuclear wastes. If we stopped doing all these things, if we just thought about the future. All these decision affect the future. So my hope for the future is that we learn wisdom again.

For more information visit the Jane Goodall Institute and Roots & Shoots.

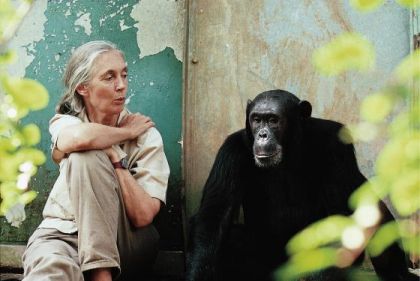

Photo of Jane Goodall (c) Michael Neugebauer

Note: This interview originally appeared at The Huffington Post

***

Jane Goodall, PhD, DBE In June 1960, Jane Goodall began her landmark study of chimpanzees in what is now Tanzania under the mentorship of famed anthropologist and paleontologist Dr. Louis Leakey. Her work at Gombe Stream would become the foundation of future primatological research and redefine the relationship between humans and animals.

In 1977, Dr. Goodall established the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI), which continues the Gombe research and is a global leader in the effort to protect chimpanzees and their habitats. Today, the Institute is widely recognized for establishing innovative, community-centered conservation and development programs in Africa, and Jane Goodall’s Roots & Shoots, JGI’s global environmental and humanitarian youth network, which has almost 150,000 members in 110 countries.

Dr. Goodall travels an average 300 days per year, speaking about the threats facing chimpanzees, other environmental crises, and her reasons for hope that humankind will solve the problems it has imposed on our planet. She continually urges her audiences to recognize their personal responsibility and ability to effect change. “Every individual counts,” she says. “Every individual has a role to play. Every individual makes a difference.”

Dr. Goodall’s scores of honors include the Medal of Tanzania, the National Geographic Society’s Hubbard Medal, Japan’s prestigious Kyoto Prize, Spain’s Prince of Asturias Award for Technical and Scientific Research, the Benjamin Franklin Medal in Life Science, and the Gandhi/King Award for Nonviolence. In April 2002, Secretary-General Kofi Annan named Dr. Goodall a United Nations Messenger of Peace, and she was reappointed in June 2007 by Secretary General Ban Ki-moon. In 2004, in a ceremony at Buckingham Palace, Dr. Goodall was invested as a Dame of the British Empire, the female equivalent of knighthood. In 2006, Dr. Goodall received the French Legion of Honor, presented by Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin, as well as the UNESCO Gold Medal Award.

Dr. Goodall’s list of publications includes Hope for Animals and Their World: How Endangered Species are Being Rescued from the Brink, Harvest for Hope: A Guide to Mindful Eating, two overviews of her work at Gombe — In the Shadow of Man and Through a Window — as well as two autobiographies in letters, the best-selling autobiography Reason for Hope and many children’s books. The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior is the definitive scientific work on chimpanzees and is the culmination of Dr. Goodall’s scientific career.

***

BACK TO INSPIRING CONVERSATIONS MAIN PAGE

Other interviews by Marianne Schnall

* * *

©Marianne Schnall. No portion of this interview may be reprinted without permission of Marianne Schnall .

Marianne Schnall is a widely published writer and interviewer. She is also the founder and Executive Director of Feminist.com and cofounder of EcoMall.com, a website promoting environmentally-friendly living. Marianne has worked for many media outlets and publications. Her interviews with well-known individuals appear at Feminist.com as well as in publications such as O, The Oprah Magazine, Glamour, In Style, The Huffington Post, the Women's Media Center, and many others.

Marianne's new book based on her

interviews, Daring to Be Ourselves: Influential Women

Share Insights on Courage, Happiness and Finding Your Own Voice came out in November 2010. Through her writings, interviews, and websites, Marianne strives to raise awareness and inspire activism around important issues and causes. For more information, visit www.marianneschnall.com and www.daringtobeourselves.com. |