|

|

|

See another section in Articles & Speeches |

|

|

Questioning Economic Success Through the Lens of Hunger

by Devaki Jain

Feminist constructions of thought have always drawn from the ground, from the experience of struggles and local initiatives. What is needed is to consolidate the revelations from these efforts into a strong, globally affirmed theory by feminists. Feminist constructions of thought have always drawn from the ground, from the experience of struggles and local initiatives. What is needed is to consolidate the revelations from these efforts into a strong, globally affirmed theory by feminists.

Excerpted from:

Harvesting Feminist Knowledge for Public Policy: Rebuilding Progress (Sage Communications © 2012)

Introduction

This chapter looks at how providing food security for all—or, to put it another way, ensuring freedom from hunger (Drèze & Sen, 1989)—can point the way toward a more humane political economy. Looking at the political economy through the lens of food fits well with the feminist concept of the intersectionality of disciplines; it falls under the human security rubric, as well as under human rights, sustainable development, and economic growth.

The meltdown of 2008–2009 has shaken the world in many ways. It was not just a global downturn in the GDP but a set of linked crises, some dimensions of which—relating to the food and fuel crises and climate change—predate the financial crisis (Jain & Elson, 2010). It has exacerbated the challenges of feeding the world, of obtaining clean water, of having sufficient energy, and of global warming and ecological disasters (FAO, 2009; Simms, 2010). It has made clearer the tensions around access to and provision of care for households and communities.

Food has been a central issue in feminist explorations of identity, stigma, and intra-household power dynamics, and hence it offers space for feminist interrogation. Food is also central to political strategies of the state as well as the household. In both of these spaces gender dynamics get played out in various ways. Using India as the landscape, and food—or better yet, hunger—as the entry point, this chapter critically explores the reasons for what can be called the Indian paradox of “mountains of food and millions of starving citizens” and suggests that:

• measures of economic success—be they GDP growth rates, capital inflows, or trade values—that fail to recognize the various nonmarket, nonmonetized values mislead and misdirect national efforts to redress hunger and poverty; and

• without the underpinning of a political and ethical philosophy toward economic justice, massive inequalities will persist despite pro-poor and welfarist policies.

With so many serious threats to human security, it is an appropriate time to revisit the ideas that Mahatma Gandhi provided for economic growth and people’s well-being. A holistic approach such as the one he offered to India and the world at the turn of the 20th century is needed to build a peaceful and just world.

Growing Global Inequality

A recent study by the World Institute for Development Economics Research of the United Nations University (UNU-WIDER) on the world distribution of household wealth (Davies et al., 2006) takes wealth (rather than income) as the parameter and finds resounding evidence that its distribution is highly concentrated, much more so than the world distribution of income. It has also been stated in unequivocal terms, “corporate globalization has been marked by greatly increased disparities, both within countries and between countries” (Edwards, 2006). A World Bank study reveals that between 1820 and 1992 the income share of the bottom 60 percent of the world’s population halved to around 10 percent while the share of the top 10 percent rose to more than 50 percent (cited in Shah, 2008).

The rise in inequality appears to be the result of three factors: a shift in earnings from labor to capital income; the rapid growth of the services sector—particularly the finance, insurance, and real estate sectors—with a consequent explosion in demand for skilled workers but reduced demand for other workers, especially women in less formal work; and a drop in the rate of labor absorption. In India, this has been happening since 1993 with the liberalization of the economy.

The gender dimension further complicates this issue as women usually do not share equitably in the wealth of men, even within the same household or family (Deere & Doss, 2006). Therefore, the gender distribution of wealth matters. The asymmetrical nature of gender relationships leads women to experience greater inequality than men; not only are more women poor, but their experience of poverty is also markedly different.

Feminist Analysis and Hunger—The Link

In a UNDP paper launched at the Beijing +15 meetings at the United Nations in March 2010, the informal group of Casablanca Dreamers (see http://www.casablanca-dream.net/index.html) proposed that the global crises of contemporary development were not only those of finance and employment but also deprivation of food, water, energy, fuel, and care as well as increasing environmental devastation—problems that had been growing for decades (Jain & Elson, 2010).

Responding to the devastating food crisis that also appeared in full fury in the same years as the financial meltdown, the Casablanca group pointed out that food economies are by and large led by women farmers,

adding, “In many developing countries, women make up over half of the agricultural work force. In some countries they are the majority of farmers” (ibid.).

But there is a gender–caste system operating here, with the lack of recognition for women as farmers still a submerged issue. Women’s association with the provisioning of food, not only as growers but as preparers, is considered one of their virtues, taken for granted, and seen as a cultural value in patriarchal societies. Thus even when a woman farmer commits suicide, it is not seen as “a farmer’s suicide.” The Casablanca group therefore continued:

It will not be enough simply to distribute more land to individual women farmers. There would be a need to direct the entire economy towards support to small farms and the kind of farming that women engage in. If the current trend is followed then in the space of a couple of decades, land would be concentrated in the hands of large commercial farmers. Better land rights for women need to be embedded in a system of equitable public support. (Jain & Elson, 2010)

In other words, they pointed to the link between women’s roles and values in a political economy and the changes in macroeconomic policy that are required. A complete reorientation of the role/location/share of agriculture in GDP—and thus a revision in the selection and prioritization of the triggers of economic success as well as the political philosophy underpinning current policy—would be a necessary condition for freedom from hunger for all.

The Situation in India

The Indian paradox is interesting to study not only because its economy has been witnessing very high rates of growth in the current decade but also because the State has engaged itself with the issues of poverty and hunger for decades. Further, despite deep flaws in its performance, it does function under the rule of law and continues to have space for the affirmation of rights, a free press, etc., that are characteristics of a democratic nation.

Real GDP in 2004 was 10.3 times of what it was in 1978. In the post-liberalization period since 1994, the country’s rate of growth of GDP has gone up from a mere 5 percent to around 8.5 percent per annum. India managed to keep up a growth rate of around 6 percent even during 2009, and in 2010 is building up to reach 8 percent again.

However, India’s excellent growth has had little impact on food security and the nutrition levels of its population (Saxena, n.d.). Per capita availability as well as consumption of foodgrains has decreased; the cereal intake of the bottom 30 percent continues to be much less than the cereal intake of the top two deciles of the population, and calorie consumption of the bottom half of the population has been consistently decreasing since 1987.

“The rich get hungrier,” says Amartya Sen (2010), answering his own question, “... will the food crisis that is menacing the lives of millions ease up—or grow worse over time?” He adds:

Though the need for huge rescue operations is urgent, the present acute crisis will eventually end. But underlying it is a basic problem that will only intensify unless we recognize it and try to remedy it. It is a tale of two peoples. In one version of the story, a country with a lot of poor people suddenly experiences fast economic expansion, but only half of the people share in the new prosperity. The favored ones spend a lot of their new income on food, and unless supply expands very quickly, prices shoot up. The rest of the poor now face higher food prices but no greater income, and begin to starve. Tragedies like this happen repeatedly in the world.

India is now home to nearly half the world’s hungry population, with the usual special assault on the female of the species. Although it has put in place a Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS)—which caters to 65 million families below the poverty line and 115 million families above the poverty line—it is ranked 65th (“alarming”) among 88 vulnerable countries in the 2008 Global Hunger Index (Von Krebmer et al., 2008). Its hunger record is worse than that of nearly 25 sub-Saharan African countries (ibid.). Around 35 percent of India’s population—350 million people—are considered food-insecure, consuming less than 80 percent of minimum energy requirements (Adil, 2008).

Along with this situation of terrible food deprivation, there are also growing inequalities related very specifically to this post “reform” period. The narrow base of economic growth focused on the service economy has meant that trickle-down theories of the spread of prosperity have remained confined to the sphere of illusions, and the magnitude and rate of change of inequalities are quite substantial. Very sharp contrasts are evident between the rural sectors of the slow-growing states and the urban sectors of the fast-growing states (Sen & Himanshu, 2004; Sinha, 2005). This rise in the incidence of rural poverty and inequality has meant that, despite better growth, poverty reduction has been sluggish (Jha, 2000). Multiple inequalities lock in the income levels of poor, disadvantaged populations in backward areas, and the effects of growth are limited to the margins of the high-growing enclaves and urban conglomerations (Sinha, 2005).

These inequalities are reflected in a number of ways. For example, the poor rural population has 230 million undernourished people—the highest for any country in the world—and 50 million Indians under five are affected by malnutrition. Malnutrition accounts for nearly 50 percent of child deaths, and every third adult (aged 15–49 years) is reported to be unacceptably thin (body mass index less than 18.5) (Sinha, 2009). Rising food prices, UNICEF says, mean 1.5 to 1.8 million more children in India could end up malnourished (ThaIndian News, 2008). More than half of India’s women and three-quarters of its children are anemic, with no decline in the last eight years.

India has a high maternal mortality rate of about 230 per 100,000 births, and had the largest number of maternal deaths (63,000) in 2008 (WHO et al., 2010). And if we delve deeper again, the story of inequality becomes even more evident—for example, one study showed that over 67 percent of maternal deaths occurred among the oppressed castes and in indigenous populations; in another district it was noted that 48 percent of the women who had died had had no formal schooling (Financial Express, 2008).

High economic growth rates have failed to improve food security in India, leaving the country facing a crisis in its rural economy (WFP & MSSRF, 2009). The number of undernourished people is rising, reversing gains made in the 1990s. The slowing growth in food production, rising unemployment, and declining purchasing power of the poor are combining to weaken the rural economy (ibid.).

With a network of more than 400,000 Fair Price Shops claiming to annually distribute commodities worth more than 150 billion INR to about 160 million families, the TPDS in India is perhaps the largest distribution network of its type in the world (in 2010, 47 Indian rupees [INR] = 1 United States dollar [USD]). These shops distribute a total of 35 kg of wheat and rice to about 65 million families below the poverty line at 4.2 INR per kg for wheat and 5.6 INR for rice (the present market rate is about double the TPDS price). Another 25 million poorest families get 35 kg of food grains at a highly subsidized rate of 2 INR per kg for wheat and 3 INR per kg for rice. In addition, there are welfare schemes such as hot cooked midday meals for school-going children and supplementary nutrition for preschool children. Yet, the “targeting of BPL (below poverty line) households has been one of the more spectacular policy failures of contemporary India” (Sharma, 2010).

What Went Wrong?

The suggestion here is that this situation of gross inequality and of hunger and extreme poverty in India is the result of contagion from the disease that is the currently operating paradigm of progress: the globalized trade, finance, and GDP growth rate-led market and monetized value-led path to economic success. Belief in the rate of growth of GDP as the sign of success, and moving away from farms and farming, neglecting the masses, and ignoring the enormous increase in disparities, are the contagion from the ideas behind the management of the global economy not only in the decades since the 1990s, but a continuum of the “modernization” project, the paradigm of progress as designed by the global North, the “advanced” countries, springing from the approach of the colonial powers.

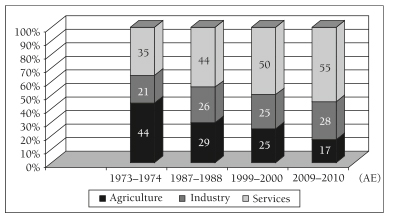

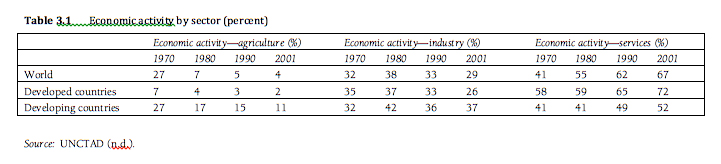

Currently, India is experiencing the pressures arising out of taking that imitative road; it has shifted its interest from the agricultural sector to services and other sectors. This shift in the share of the three sectors in GDP is a worldwide phenomenon, as can be seen in the Figure 3.1 and Table 3.1. Figure 3.1 shows the shift in the GDP composition of India from 1973 to 2010.

Figure 3.1 GDP by economic activity (percent)

Source: Computed from Government of India (2010).

Note: The author would like to thank Divya Alexander for her assistance in preparation of the figure.

Table 3.1 reflects the same issue of shifts—from agriculture to services—in the composition of GDP at the global level from 1970 to 2001.

It will be noticed that in all the categories of countries, labor has shifted downward in agriculture, though more dramatically in the other regions than the developing countries. This movement away from agriculture, it is argued, has been responsible for the crisis in food security worldwide. The United Nations has estimated the total number of food insecure people at close to 3 billion, or about half the world’s population (UN, 2008). The early years of the 21st century have seen hungry people rioting in 37 countries. There is a shift toward greater market orientation at the macro level, which is also reflected at the micro level, with people increasingly moving out of subsistence production and into production for the market, which often means moving away from basic food crops to crops for the higher income classes. This trend is being reinforced by micro-level interventions, such as credit delivery programs that encourage poor households to engage in market-oriented production.

Within India this crisis in agriculture is a direct offshoot of the change in priorities during the early 1990s. Growing obsession with the so-called “new economy,” information technology, media, and the urban consumer has led to the marginalization of the rural and agrarian sector, with respect to both private and public sector investment. Simultaneously, a greater proportion of the land used for agricultural purposes is now devoted to nonfood agriculture (Sundaram, 2008). One million hectare has gone out of cultivation in recent years in India and much more is threatened.

A recent example is the subsidies that the government of Maharashtra is offering for liqor production from food grains, especially sorghum—known locally as jowar—the cereal of poor households and also a dry land crop. This policy will turn jowar into a cash crop and divert huge quantities of food grains to alcohol production, creating scarcity and causing food inflation. Moreover, Right to Information (RTI) documents have revealed the falsity of the claims made by the government as to the project’s benefits: distilleries are purchasing grains from dealers and not from farmers.

Rather than focusing on the acute problem of malnutrition plaguing the state, the government is promoting a policy that is clearly meant to benefit only those with business interests (Tiwale, 2010).

The policies of economic liberalization have also required all sectors of the Indian economy to be opened up to global markets. Opening up the farm sector, in a country where the predominant structure of agricultural production is small-size holdings (as opposed to plantation economies), has undermined the viability of small farms and food farming. Corporate-driven agriculture, camouflaged with misinformation as to the threat that it posed, treated farmers as recipients and not as partners in the process (Ramprasad, 2008). The further erosion of the opportunity and space for small farmers is the argument that introducing retail trade chains—through what in India is called bringing foreign direct investment (FDI) into the food sector—will assist them in their marketing. Evidence from the United States and other countries clearly shows that this arrangement basically disempowers the farmers and is a profit-enabling mechanism for the retail chain (Chandrasekhar & Ghosh, 2009; DFID & IIED, 2004).

The Gender Dimension

This withdrawal from the food-driven economy, or land being used for food, as well as the intensification of inequality are acutely gendered. As noted earlier, food is central to political strategies of the state as well as the household. In both of these spaces gender dynamics get played out in various ways. Within the household, women’s sense of accomplishment is linked to feeding her family a satisfying meal, even while she eats last or starves.

The agricultural sector is the largest employer of women in India. According to official statistics, women make up 32 percent of the country’s total workforce, and of this 84 percent work in rural areas. Men have been steadily moving out of the agricultural sector into more diversified occupations; by 2004–2005, only 66.5 percent male workers were in agriculture compared to 83.3 percent female workers (Srivastava & Srivastava, 2009). This adds to the responsibility and strain on women to provide for the household, within an increasingly neglected part of the economy (Kanchi, 2009).

Given women’s role in food production and provision, any set of strategies for sustainable food security must address their limited access to productive resources. Crucial to their access to resources is ownership of land; providing land rights for women is the very first need for food security for all. Women’s limited access to resources and their insufficient purchasing power are products of a series of interrelated social, economic, and cultural factors that force them into a subordinate role to the detriment of their own development and that of society as a whole.

The volatility of prices of agricultural products and fuel due to the liberalization of international trade, the withdrawal of input subsidies and contraction of the public distribution system, environmental stress, and climate change are some of the other factors originating outside the sector that compromise women’s capacity to ensure household food security (ibid.).

Inequity in access to common resources—water bodies, forests, and grazing grounds—affects women in cultivating, casual labor, and above all, landless labor households. A study in seven states in semiarid regions showed that common property resources accounted for 9 to 26 percent of household income of landless and marginal farmers, 69 to 89 percent of their grazing requirements, and 91 to 100 percent of their fuel requirements (Bandyopadhyay, 2008).

Restriction of access to community resources not only robs women of opportunities for diversification into livestock and collection of non-timber forest products, but also adds to their work burden by increasing the distance traversed and time required for collecting fuel for cooking and water for drinking. For women, agricultural work, informal work, landlessness, discrimination, and poverty mesh into a connected web.

Was There Another Way? There Was

With independence in 1947, India inherited a heady cocktail of ideas for its regeneration. Inevitably, the economic exploitation-centered nature of colonial rule and consequent destitution of the people drove many political leaders of the liberation movement to try and free the masses from both the political oppression of the colonizer as well as the oppression of deep material deprivation. The latter was called the second freedom: freedom from economic exploitation. In this quest, there was a natural rejection of European culture and an affirmation of the country’s own civilization, as well as its people’s skills.

Like some of the leaders of freedom struggles in other countries, Gandhi wanted, when rejecting the colonial masters, to also reject their notions and strategies for progress. He had already described himself, in 1914, as “an uncompromising enemy of the present day civilisation in Europe” and rejected the so-called success story of industrialization and “modernization” (Johnson, 2006). When asked by a British journalist whether he would like India to have the same standard of living as Britain, he replied that considering that such a small island had to exploit half the globe to have this living standard, there were not enough globes for a big country like India (ibid.).

Revolting against the exploitative nature of the build-up of the West’s industrial and technological strength, Gandhi argued that Indian ideas in Indian conditions were necessary to relieve the masses from the burden of economic oppression in the shortest time, with tools and techniques that were labor-absorbing and used minimum capital and energy. He was also, perhaps, one of the first to understand the nature of roving capital, and how it can not only exploit for self-advantage the resources of the colonies, but also subordinate the mind of the colonized and gain partners among them.

Gandhi suggested that production and consumption should be proximate and based as far as possible on local resources, “the first concern of every village republic will be to grow its own food crops and cloth” (Kripalani, 1970). To provide dynamic institutional underpinning to operationalize these ideas on the ground, Gandhi held that a unified political and economic strategy was required. This entailed the creation of an institution in the political realm, “village republics,” to ensure that every adult had an equal share of political power as well as the duty to be an active custodian of political freedom. Swaraj, self-rule, was applied at all levels: Hind swaraj, self-rule for India; gram swaraj, self-rule for the village; and swa-dharma, self-rule for the individual. One could suggest that this was similar to or the same as affirming individual rights.

Interestingly similar ideals were put forward by leaders of freedom struggles elsewhere. For example, Julius Nyerere led a socialist economic program in Tanzania (announced in the Arusha Declaration), establishing close ties with China, and also introduced a policy of collectivization in the country’s agricultural system, known as ujamaa (familyhood or extended family). He had tremendous faith in rural African people and their traditional values and ways of life. He believed that life should be structured around the ujamaa found in traditional Africa before the arrival of the imperialists.

The kibbutzim in Israel was a post-liberation idea using the same concept of collective ownership, attempting to efface inequality among Jewish settlers through collectivity (but not through force, as in the Soviet Union, but as a form of “voluntary mobilization”). So Gandhi’s ideas for village-level governance really were resonating with what other leaders post-liberation were attempting: to bring back the community spirit of the pre-imperial days.

Initially, when India became independent in 1947, agriculture, the poor, employment, state intervention in ensuring security were the basis of policy. Land reforms, such that large land holdings were to be distributed and rights over land given to peasants, were also on the agenda. The Constitution guaranteed these rights.

However, as well as causing a move away from agriculture, the food distribution policies and practices did not work. Those who are trying to use the rights framework to correct India’s wrongs to the poor and the hungry are now re-invoking Gandhi. First, the Supreme Court commissioner on the right to food in India, Harsh Mander, affirms that the paradox of a country with high growth producing enough food to feed all its people, and yet having greater hunger and malnutrition than much poorer countries, is due to the systematic destruction of the livelihoods of small producers—farm workers, artisans, and small traders—as well as great gender and social barriers (Mander, forthcoming). He suggests the relevance of Gandhi and his focus on the “last person,” the least privileged (ibid.).

Second, research shows that small farms are capable of high productivity through intense husbandry and family motivation (OneWorld UK, 2009). Those who are promoting the alternative philosophy of “food sovereignty” favor local ownership and control of the full chain of resources. Small farms, they argue, can deliver the added value of reducing the contribution of agriculture to climate change. Low-input ecological or organic farming avoids fuel-dependent inputs in favor of soil carbon sequestration and sustainable water management (ibid.).

Third, support for the idea of greater control by local communities over the production, storage, and distribution of food is gaining ground everywhere, and many examples of how this is done are being invoked at all levels of knowledge. These include community grain banks to which farmers give grain in times of plenty and from which they borrow in times of need; seed banks to reduce dependence on moneylenders and local suppliers; local community food production planning by small and middle farmers; community irrigation schemes and pani panchayats, or water collectives, for the sustainable and equitable use of water for food production; ration shops run by panchayats or Self-help Groups (SHGs) of women; local procurement for the TPDS, and also other food-transfer schemes such as Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) and midday school meals; and production and distribution of school meals as well as weaning foods as part of these services by women’s SHGs—so many examples abound in India as they do elsewhere (Mander, 2009). One of them is described in Box 3.1.

Box 3.1 RUDI: A sustainable local procurement and distribution system

RUDI is the acronym for a project being run by the Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) in Gujarat. Excess farm produce is procured at fair market prices from marginal farmers, and women then clean, grade, sieve, grind, weigh, pack, and label it. It is then sold in the villages at competitive prices. RUDI’s portfolio of products is based on the needs of its rural consumers, and the products are priced according to the purchasing power of poor households. By procuring products locally, and processing them and distributing them locally, RUDI has created a sustainable ecosystem at the village and block level, a model that can be replicated and expanded seamlessly.

Following this experience, and the ideas drawn from Gandhi, SEWA critiques the current concept of the Right to Food Act and asks for proximate linking between producers and consumers. Through RUDI, SEWA argues for initiatives incorporating local procurement and distribution as this creates a sustainable economy at the local level, creates equitable access to essential goods, while at the same time generating the purchasing power required to purchase these goods.

Source: Note by Reema Nanavaty, Chair, RUDI.

However, there are questions and challenges in that the ways by which this can be achieved in the complex world of globalized markets are hard to find. This is where the recognition of the need for a sea change in global economic reasoning and policy becomes critical for the local to flourish as an alternative to the global—or as the basics, as Gandhi would have argued.

This idea of local initiatives and circulation of production and exchange is resonating in global reports too. The 2008 World Development Report, for example, says, “GDP growth originating in agriculture is at least twice as effective in reducing poverty as GDP growth originating outside agriculture” (World Bank, 2007). Moreover, the UN adds regarding Africa:

… the implementation and scaling up of initiatives to support improved agricultural productivity, particularly amongst smallholder farmers, will be critical to speeding growth, increasing incomes and improving the lives of the continent’s people. With the assistance of the international community, rural producers who are the prime victims of the present crisis can become the prime actors of its solution. (NGLS, 2008)

These views bring back the relevance of the Gandhian package for freedom from hunger and the building of a just and equitable society. This is not fragmented to deal with specifics but is founded on an overall approach to what is economic and political progress, enshrining individual rights and sovereignty but ensuring that the basics—food, clothing, shelter, and the right for self-determination—are there. The measures of success are not the rate of growth of GDP or the value of trade but the spread of well-being. It is thus in direct conflict with the ideas that are now seen as leading to economic success.

Changing the Measurement of Progress

In his seminal work Development as Freedom, Amartya Sen (1999) contrasts the remarkable economic progress and wealth created in the last century to the devastating deprivation, destitution, and oppression suffered by billions of people worldwide, especially women and children. He argues for an integrative framework in economics that moves the focus from market expansion to the improvement of individual lives, which will invariably lead to sustainable economic growth.

The current crisis can thus be seen as an opportunity to move away from the export-led model in developing countries and focus on domestic and/or regional markets, especially the food segments where small-scale producers are concentrated. Whether sold or donated, cheap food from the West has almost always undercut, damaged, and skewed agriculture in poor countries by pricing local farmers out of the market. As a result, Western farmers and agriculture have political weight far beyond their contemporary economic importance.

But the debates—whether in the G20 or other global forums as well as within countries—continue to spin around exports, capital inflow of FDI, and rates of GDP growth as the health of a nation. Neither the hunger index nor the unemployment index nor the inequality index is being seriously used to measure progress, despite statements by high-profile economists such as Joseph Stiglitz:

If we have poor measures, what we strive to do (say, increase GDP) may actually contribute to a worsening of living standards …. Statistical frameworks are intended to summarize what is going on in our complex society in a few easily interpretable numbers. It should have been obvious that one couldn’t reduce everything to a single number, GDP. (Stiglitz, 2009)

Moreover, the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress (the Sarkozy Commission, created at the beginning of 2008 on the initiative of the French Government) has merely added a few more indicators to deepen the knowledge on what is happening, rather than decoding GDP. It is also not addressing the basic triggers of growth as currently used, namely capital-led, corporate-led, competition-led production and trade.

Feminists have also engaged with the idea of measures. Braunstein & Folbre (2001) and Eisler (2007), for example, do not discount the value of GDP as an economic indicator but argue that it does not give a full and accurate assessment of a country’s economic production and condition. Eisler emphasizes the need to measure the status of women and children as fundamental indicators of the well-being and economic strength of societies. Her main critique of GDP is that it does not fully account for all economic activities, especially those that exist outside the realm of monetary exchange. For instance, GDP does not add in the monetary value of “the caring economy”—the unpaid care of households, children, the elderly, the sick, and the disabled—by family members, usually women.

Others have also noted that GDP does not take into account the work done within families and communities for free (Rowe, 2008). Still others argue that not only is GDP inadequate as an economic index, it simply fails as a measure of social welfare. But in all this work, the underpinnings of economic reasoning—the questions of for whom the economy is being run or developed and where is the trigger to start an engine that can lead to more widespread economic prosperity toward a just society—do not get addressed.

Yet this is what Gandhi did. We all know Gandhi’s basic recommendation to start with the poor and his mantra on how we choose the path to shared prosperity. But whereas most economic progress theories begin with production and surplus from which distribution would take place, called the “trickle down” theory of growth and currently predominant in India, Gandhi’s prescription could be seen as the “bubble up” theory of growth.

This approach would argue that the process of removing poverty can itself be an engine of growth; that the incomes and capabilities of those who are currently poor have the potential to generate demand that in turn will be an engine of production. However, this production would be specifically of goods that are immediately needed by the poor, which are currently peripheral in production. The oiling of this engine will bubble up and fire the economy in a much more broad-based manner. Unlike export-led growth, it will not skew production and trade into the elite trap, which is accentuating disparities and creating discontent.

Looking back from India’s current situation of the striking exclusion of the poor from the agenda, as well as the co-option by the elite of the fruits of growth, and the subordination to the old paradigm of modernization and “progress,” the value of Gandhi’s economics is that it starts from distribution and leads through the foundation of individual freedom and individual rights to self-determination. Its formulae are very similar to the ones being put forward by those working for the right to food and for sovereignty.

While colonial Europe used to talk of rights in terms of rights over territory and the population of nation–states, the anticolonial struggles have turned the term against their colonial masters to stress the rights of the colonized to control their own political and economic structures and systems. The term is revisited now in an era of transnational powers to bring in notions of self-determination of communities and peoples, especially the marginalized.

Within the debate on food, the idea of sovereignty is linked to bio-politics. The global South has seen a huge rise in social movements contesting corporate globalization’s control over food, even while confronted with accusations of backwardness and utopianism as well as the assumption that there is no turning back. The message from these struggles is basically of food sovereignty, affirming the right of every population to decide what to eat and how to produce it in a way that is equitable, just, and sustainable. Very clearly, those who control food production also control the political economy of the planet (Caffentzis, 2008).

One specific policy that could be put in place today to make India less punishing for the poor—and drawn from Gandhi’s ideas—is that of localizing food self-sufficiency. Given that the major part of India’s labor is still in rural areas, where 84 percent of the female workforce is toiling, and given that we have the germ or nucleus for gram swaraj in the panchayati raj institutions that were put in place by Rajiv Gandhi, it would not be impossible to start from the poor and follow a Gandhian program from the village upwards.

For example, a present-day Gandhian feminist, Ela Bhatt, makes a proposal to implement Gandhi’s production/consumption cycle within a geographical space. She calls it the 100-mile principle for economic security for the poor (see Box 3.2). Putting it into general practice would require a total turnaround from what is catching the imagination of political leaders today. Yet it shows the way, and feminist movements and networks, working together, need to and can rewrite economic success through ideas such as this.

Box 3.2 The 100-mile principle for economic security

The 100-mile principle weaves decentralization, locality, size, and scale to livelihood. What one needs for livelihood as material, as energy, as knowledge should stem from areas around us. Seed, soil, water are forms of knowledge that need to be retained locally. Security stems from local innovations, not distant imports. The millennia-old link between production and consumption has to be recovered. 100-mile is a threshold principle. It shows when you export food or import seed you deculturate a community. Take food. Is it grown and cooked locally? How many energy miles has it consumed? Unless food is grown locally, you cannot sustain diversity. Food has to be grown locally, made locally. Ask yourself what happened to local fruits, local foods like barley, and local staples like cotton. But when food is produced locally and exported, the locality has no access to its own labor, to its produce. You grow milk and vegetables for the city and survive on less. Freedom is the right to your labor, your produce. Such a freedom needs a community. A community is autonomous when it controls food, clothing, shelter (roti, kapda, makan). This old cliché of roti, kapda, makan has to be within a 100-mile radius. The minute you extend the production cycle you lose control.

Comparative advantage might be good economics but let us leave well-intentioned economics outside communities. Otherwise, instead of freedom, we face obsolescence. When food is exported, when technology is centralized, when shelter depends on some remote housing policy, we lose our freedom as a community. 100-mile is a guarantee that citizens retain control, inventiveness, diversity. We could grow 50,000 varieties of rice because we followed the 100-mile principle intuitively.

Source: Bhatt (2009).

Much of India’s industrial output comes from the informal economy—from home-based work with no security, either economic or legal, in terms of labor laws. A strong revivalism of the handmade product industries, as well as own enterprises, could both provide security as well as ensure GDP with justice. Such a thrust would require complex undoing of not only tax and credit policies, but also trade policies, approaches to infrastructure development, and licensing laws, to mention a few areas.

A village plan that starts with the poor mapping out the structure and shape of their existing sources of livelihood through products that are unique, including growing foodgrains that are appropriate to the local area, and enabling their circulation through local marketplaces, means beginning at the bottom. A strong push with backward–forward linkages to the industrial goods that hands make—handmade products that often are not only the major proportion of domestically used goods but are also exportable, such as diamonds or embroidered goods being produced in many other developing countries apart from India—would create another cycle of growth with employment.

Conclusion

A strong political move is needed by women to reclaim democracy and development through the mobilization of those engaged locally, through the concepts of the inverted pyramid and of “think locally and act globally” (not the other way around), bubbling up to become a tidal wave at the macro or global level (Jain & Chacko, 2007). By identifying ourselves with justice and inequality, with the downtrodden as Gandhi would say, or the discriminated against and the hungry, by having a vision, as many feminists have argued, and by superseding all the challenges to forging identity, such as gender or race, we may be able to build our voice. To challenge androcentric and eurocentric knowledge, we need to rebuild knowledge together as a bonding process for building political solidarity.

However, for this to replace the old model of production, of surplus then distribution—for it to give space both to environmental protection as well as economic security for the masses, especially women among them—the underlying principles of what makes for progress need drastic revision. Feminist constructions of thought have always drawn from the ground, from the experience of struggles and local initiatives. What is needed is to consolidate the revelations from these efforts into a strong, globally affirmed theory by feminists.

The Indian experience, both in its inspiration from Gandhi and its enslavement to the current impulses and measures of success, offers a lesson or a path for feminists building alternative economic models to consider.

Excerpted from:

HARVESTING FEMINIST KNOWLEDGE FOR PUBLIC POLICY

Rebuilding Progress

edited by: DEVAKI JAIN Founder and former Director, Institute of Social Studies Trust, New Delhi, India

DIANE ELSON University of Essex, UK

2011 / 396 pages / Hardback: Rs 795 (9788132107415)

SAGE Publications

Related links at Feminist.com:

Highlights of Remarks by Devaki Jain at Feminist.com's FemSalon on Feminism (Video)

Devaki Jain is a development economist and activist. She graduated in Economics from Oxford in 1963 and taught at Delhi University for 6 years. Since then, her academic research and advocacy, influenced largely by Gandhian Philosophy, have focussed on issues of equity, democratic decentralisation, people centred development and women's rights. Devaki Jain is a development economist and activist. She graduated in Economics from Oxford in 1963 and taught at Delhi University for 6 years. Since then, her academic research and advocacy, influenced largely by Gandhian Philosophy, have focussed on issues of equity, democratic decentralisation, people centred development and women's rights.

She was one of the founders of a wide range of institutions such as Development Alternatives for Women for a new Era (DAWN) - a third world network of women social scientists who provided an alternative framework for understanding the location of advancing the cause of poor women of the South. Indian Association of Women's Studies (IAWS), Kali, Feminist Publishing House and Institute of Social Studies Trust (ISST) - a research centre in Delhi where she was Director until 1994. She was a member of the erstwhile South Commission, established in 1987 chaired by Dr. Julius Nyerere and various other committees/agencies such as the Advisory Committee for UNDP Human Development Report on Poverty, 1997; the Eminent Persons group associated with the Graca Machel Committee (UN) on the Impact on children of Armed Conflict etc.

She is one of the two women awarded the Bradford Morse Memorial Award by the United Nations at the World Conference at Beijing for outstanding achievements through professional and voluntary activities in promoting the advancement of women and gender equality for 20 years.

She has been an active member of the Women's Movement - local, national and worldwide through women's organisations and networks. She studied and enabled many grassroot women's organisations such as SEWA Ahmedabad, to articulate their voices to be visible in the broader landscapes. She is also involved with alliances and coalitions of community movements such as Nationals Alliance of People's Movements" (NAPM); the National Centre for Labour (NCL) a coalition of unions of unorganised labour. She is a founder member of the International Network for Engineers and Scientists-INES -an outcome of the Scientists for Peace Initiatives of Bertrand Russell.

She has also served on the National Preparatory Committee set up by the Government of India to prepare for the UN World Conferences, notably, Nairobi (women),1985; Cairo (population)1995 ; and Beijing(women) 1995. She has been a member of many policy and programme designing task forces and working groups set up, with special reference to women' s economic empowerment, by the Government of India such as the Ministry of Rural Development to design credit programmes for Rural Women; Member of the Core Committee to set up the National Women's Resource Centre (Ministry of Human Resource Development). At the Central Planning Commission, she has been a member of the group set up to draft the Women's Development Chapter. She was an Adviser and Convenor of Expert group on Economic Affairs at the National Commission for Women. www.devakijain.com

References and Select Bibliography

Adil, A. (2008). India’s export ban on food grain: A measure to ensure availability of food for its poorest citizens. California: The Oakland Institute.

Bandyopadhyay, D. (2008). Does land still matter? Economic and Political Weekly, March 8, 37–42.

Bhatt, E. (2009). Citizenship of marginals. Third R. K. Talwar Memorial Lecture, Indian Institute of Banking and Finance, Mumbai, July 23.

Braunstein, E., & Folbre, N. (2001). To honor and obey: Efficiency, inequality, and patriarchal property rights. Feminist Economics, 7(1), 25–44.

Caffentzis, G. (2008). Descrambling the “food crisis.” Mute, August 26. Retrieved February 8, 2010, from http://www.metamute.org/en/content/decoding_the_food_crisis

Chandrasekhar, C. P., & Ghosh, J. 2009. Corporatisation of agriculture. Lok Samvad. Retrieved February 7, 2010, from http://loksamvad.org/e107_plugins/content/content.php?content.82

Davies, J. B., Sandstrom, S., Shorrocks, A., & Wolff, E. N. (2006). The world distribution of household wealth. World Institute for Development Economics Research of the United Nations University (UNU-WIDER), Helsinki, December 5.

Deere, C. D., & Doss, C. R. (2006). Gender and the distribution of wealth in developing countries. UNU-WIDER Research Paper No. 2006/115, October 2.

DFID (UK Department for International Development), & IIED (International Institute for Environment and Development). (2004). Concentration in food supply and retail chains. Working Paper, DFID, London. Retrieved August 12, 2010, from http://dfid-agriculture-consultation.nri.org/summaries/wp13.pdf

Drèze, J., & Sen, A. (1989). Hunger and public action. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Edwards, P. (2006). Examining inequality: Who really benefits from global growth? World Development, 34(10), 1667–1695.

Eisler, R. (2007). The real wealth of nations: Creating a caring economics. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization). (2009). The state of food insecurity in the world: Economic crisis––impacts and lessons learned. Rome: Economic and Social Development Department, FAO.

Financial Express. (2008, October 7). Maternal mortality: This India story is a shame! Financial Express. Retrieved February 3, 2010, from http://www.financialexpress.com/news/Maternal-mortality-This-India-story-is-a-shame/370599

Government of India. (2010). Press note: Advance estimates of national income, 2009–10. Press Information Bureau, Central Statistical Organization, February 8. Retrieved October 20, 2010, from http://mospi.nic.in/Mospi_New/upload/adv_rel_pressnote_8feb10.pdf

Jain, D., & Chacko, S. (2007). Shifting our platform in response to current ground-level phenomena. Paper prepared for Current Developments on Issues Pertaining to Rural Women, 4th World Congress of Rural Women, Durban, South Africa, April 23–26.

Jain, D., & Elson, D. (in collaboration with the Casablanca Dreamers). (2010). Vision for a better world: From economic crisis to equality. New York: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP).

Jha, R. (2000). Reducing poverty and inequality in India: Has liberalization helped? Paper prepared for the World Institute for Development Economics Research (WIDER) project on Rising Income Inequality and Poverty Reduction: Are They Compatible? Retrieved February 2, 2010, from http://rspas.anu.edu.au/economics/publish/papers/wp2002/wp-econ-2002-04.pdf

Johnson, R. L. (Ed.). (2006). Gandhi’s experiments with truth: Essential writings by and about Mahatma Gandhi. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

Kanchi, A. (2009). Women’s work in agriculture––expanding responsibilities, shrinking opportunities. ILO Working Paper. International Labour Organization, Geneva.

Kripalani, J. B. (1970). Gandhi: His life and thought. Ahmedabad: Navjivan.

Mander, H. (2009). Fear and forgiveness: The aftermath of massacre. New Delhi: Penguin Books India.

———. (Forthcoming). A fistful of rice. New Delhi: Penguin Books India.

NGLS (UN Non-governmental Liaison Service). (2008). Smallholder farmers hold solution to global food crisis. Media Advisory, September 16. Retrieved October 18, 2010, from http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2008highlevel/pdf/MEDIA%20ADVISORY_smallholder%20farmers.pdf

OneWorld UK. (2009). Time to attack hunger’s root causes––UN. June 10. Retrieved November 2,

2010, from http://us.oneworld.net/article/364288-global-action-needed-food-security

Ramprasad, V. (2008, October 16). The polemic of global food economy. Deccan Herald.

Rowe, J. (2008). Rethinking the gross domestic product as a measurement of national strength. Testimony before the Subcommittee on Interstate Commerce, United States Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation. March 12.

Saxena, Naresh C. (n.d.). Hunger, under-nutrition and food security in India. Retrieved January 30,

2010, from http://www.dfid.gov.uk/r4d/PDF/Outputs/ChronicPoverty_RC/CPRC-IIPA44.pdf. Working paper 44, Chronic Poverty Research Centre, Indian Institute of Public Administration, New Delhi.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. New York: Knopf.

———. (2010, May 28). The rich get hungrier [Op-ed]. New York Times.

Sen, A., & Himanshu. (2004). Poverty and inequality in India—I. Economic and Political Weekly, September 18, 4247–4263.

Shah, M. (2008, October 21). Cutting off the chain of hate. The Hindu.

Sharma, D. (2009, July 17). Food for all? Not through the NFSA. India Together. Retrieved November 2, 2010, from http://www.indiatogether.org/2009/jul/dsh-nfsa.htm

———. (2010, October, 28). What size is your hunger? S, M, XL? The Asian Age.

Simms, A. (2010, January 25). Growth is good… isn’t it? The Guardian. Retrieved January 29,

2010, from http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/cif-green/2010/jan/25/uk-growth-energy-resources-boundaries

Sinha, A. (2005). Globalization, rising inequality, and new insecurities in India. Retrieved February 2, 2010, from http://209.235.207.197/imgtest/TaskForceDiffIneqDevSinha.pdf

Sinha, K. (2009, February 27). India tops world hunger chart. The Times of India.

Srivastava, N., & Srivastava, R. (2009). Women, work, and employment outcomes in rural India. Paper presented at the FAO-IFAD-ILO Workshop on Gaps, trends and current research in gender dimensions of agricultural and rural employment: differentiated pathways out of poverty, Rome, March 31–April 2.

Stiglitz, J. (2009). GDP fetishism. Project Syndicate, September 17. Retrieved October 20, 2010, from http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/stiglitz116/English

Sundaram, J. K. (2008). Statement by the UN Assistant Secretary General for Economic Development. Press conference on World Economic Situation and Prospects, New York, May 15.

ThaIndian News. (2008). India has worst indicator of child malnutrition: Unicef. May 14. Retrieved February 3, 2010, from http://www.thaindian.com/newsportal/india-news/india-has-worst-indicator-of-child-malnutrition-unicef_10048495.html

Tiwale, S. (2010). Foodgrain vs liquor: Maharashtra under crisis. Economic and Political Weekly, 45(22), 19–21.

UN (United Nations). (2008). World economic situation and prospects (WESP) 2008. New York: United Nations.

UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development). (n.d.). UNCTAD handbook of statistics on-line. Retrieved February 8, 2010, from http://www.unctad.org/Templates/Page.asp?intItemID=1890

Von Krebmer, K., Fritschel, H, Nestorova, B., Olofinbiyi, T., Pandya-Lorch, R., & Yohannes, Y. (2008). Global hunger index: The challenge of hunger 2008. Welthungerhilfe, Bonn; International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), Washington, DC; Concern Worldwide, Dublin.

WFP (World Food Programme), MSSRF (M S Swaminathan Research Foundation). (2009). Report on the state of food insecurity in rural India. Retrieved August 11, 2010, from http://home.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/newsroom/wfp197348.pdf

WHO (World Health Organization), United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Population Fund (UNPFA), & the World Bank. (2010). Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2008. WHO, Geneva. Retrieved October 19, 2010, from http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241500265_eng.pdf

World Bank. (2007). World development report 2008: Agricultural development. Washington, DC: World Bank. Retrieved August 11, 2010, from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWDR2008/Resources/WDR_00_book.pdf |